Civil Discourse

-Mark Haeussler, CEO, Alpine Leadership

Civil discourse is the combination of being a good townsman and being committed to seeking a new truth. As not all topics are easy, leaders have a responsibility to effectively lead difficult conversations to move issues forward in a way that can engage others to generate new perspectives. Without civility, people will not listen and instead entrench further into their own views. Deep and challenging conversations are needed in any group: family, work, and community. All of these structures manage complexity and change, and the more effective the members can get closer to a mutual truth, the more effectively they can organize toward positive outcomes.

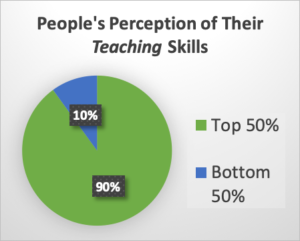

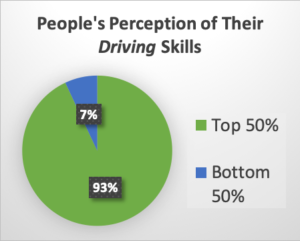

Humans need a strong ability to listen to diverse perspectives because humans are not particularly good at judging their own abilities. There are a number of ways in which even the smartest people fall into self-deception, usually a positive illusion. This cognitive bias is the Lake WobegonEffect, the fictional town created by Garrison Keillor where, “All the women are strong, all the men are good looking, and all the children are above average.”

Human brains can create a self-constructed positive trickery. This trickery seems absurd to  most people, but consider the data below, showing how we overestimate abilities:

most people, but consider the data below, showing how we overestimate abilities:

Civil discourse requires participants to blend appropriate manners with commitment. A discourse is seeking a new level of truth in the context of a commitment. The underlying commitment required is that the parties need to speak toward a commitment; otherwise, the conversation is merely complaint. The practice of discourse is having ideas exposed to further vetting to  challenge the existing truths, refine them further, or to explore and build new possibilities and new truths. To form new insights, we may have to sail beyond the ability to see our current shore, our current perspective.

challenge the existing truths, refine them further, or to explore and build new possibilities and new truths. To form new insights, we may have to sail beyond the ability to see our current shore, our current perspective.

While we all could use a full serving of humility as a start, there are some ways to approach a conversation that can create more opening for yourself and others:

- Good Intention: Assume that others come to the conversation with a good intention.

- Winning is Not the Object: Let go of winning, and frame conversations as mutual discovery. Listen to learn, and not to rebut.

- Style Preferences: Each person in a conversation has their own communication preference for speaking and listening. Be willing to meet people in their style and not make our own preference a requirement for everyone else.

- Listening at Rest: We often listen with a busy mind and a busy body. Plant your feet on the floor and pay attention to your breathing. As your thoughts come rushing in, tell yourself, “not right now,” so you can pay attention to the speaker.

- Listen More, Speak Less: If you are conducting a one-hour meeting on a subject with 6 total people in the room, that leaves less than ten minutes per person; the leader should not dominate that time.

- Ask Questions to Uncover: Pay attention to what questions you want to ask and how you ask them. Use “Why” questions sparingly, as they can make people defensive. For example, “Why do you think that?” can be reframed into “What makes you come to that conclusion.” Both questions will help you deepen your understanding, but if you create defensiveness in how you ask, it will take longer.

- Leaders Need Assessments: The data says so. And leaders askthose they lead for assessments. That is, after all, why you hired them in the first place.

More than anything, be willing to be disturbed. Being disturbed is having a familiar pattern disrupted, and that is at the core of leadership and of generative conversation. Is being certain more important than being unsettled? Being unsettled provides the fertile ground for new ideas to germinate. Listening is harder work than speaking. Think about it: when we speak, we only need to form our own thoughts into words. When we listen, we set aside our current worldview, allow for some thought-quakes inside our head, ask good questions, and then, perhaps, form entirely new thoughts. While we may fear being “wrong”, what we should pursue in conversation is a new level of understanding, a new level of “truth.” The purpose of any leadership conversation is to disturbthe current thinking and perceptions such that there are better solutions and better futures.